— figuras folclóricas de discusión pública; my own personal canon

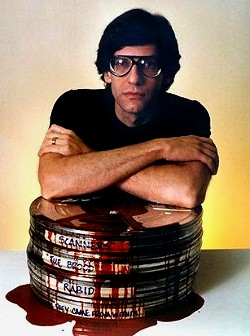

A continuación reproducimos una reflexión muy atinada sobre la entonces naciente filmografía de uno de los realizadores más representativos de los últimos 40 años en el avant-garde cinema: David Cronenberg, cuya obra, en palabras del legendario Martin Scorsese, nos sofoca con una mezcla de atrevimiento, repudio, audacia e ingenio que es contagiosa, intrigante y que continúa siendo seductora hasta nuestros días.

– – – – – – – – – –

Internal Metaphors, External Horror

Por Martin Scorsese

It was opening night, a very august occasion at the 1975 Edinburgh Film Festival. I showed up for a retrospective of my films – all two of them – and attended opening night out of a sense of ceremony. I never look forward to opening nights at film festivals. They’re like fund-raising rallies, and the movies they show on those occasions usually have titles like `How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman’. They’re usually movies that almost everyone can like, at least a little bit. In Edinburgh, that year, the opening attraction was the work of someone I’d never heard of – nothing unusual in that – named David Cronenberg. The title was The Parasite Murders (Shivers). This was beginning to sound interesting.

The festival director, Lynda Myles, had assured me that there was `a Cronenberg cult’ and that `word-of-mouth’ (or ‘W.o.m.’ to certain sordid Hollywood types) was `to say the least, unusual’. This was beginning to sound very interesting.

I took my opening night seat and watched the credits, which looked like a commercial on a local late-night movie. Then, after the credits, I watched a little more and started to wonder what this Cronenberg cult could have looked like. Thick glasses, runny noses, celibate since birth and probably Communists, for all we knew.

I made it through the rest of the movie in an ever increasing stupor of shock and depression. When it ended, I thought I didn’t like it. But a year later, I found myself still thinking about it and talking about it to anyone who would listen. To be blunt, there were a lot of people who wouldn’t listen. Cronenberg was a strange name, and my friends were dubious about the Canadian cinema anyway. Still, I kept talking, maybe as a way of exorcising Cronenberg images.

Well, I’ve never exorcised any of them. The last scene of The Parasite Murders, with the cast going out to infect the entire world with sexual dementia, is something I’ve never been able to shake. It’s an ending that is genuinely shocking, subversive, surrealistic and probably something we all deserve.

It did seem to take a little while for the word on Cronenberg to get around, though. Maybe the Cronenberg cult was too wrapped up with other things – like maybe mass murder – to go out and preach the gospel, although there was word of other Cronenberg films. These, of course, were impossible to see.

Anyway, by 1978, when The Last Waltz played the Toronto Film Festival, I was asked if there were any Canadian film-makers I’d especially like to invite to the showing. I told my friend Robbie Robertson, who was at the Canadian Film Awards as a juror (a pretty amusing concept in itself), to invite Cronenberg. I was getting annoyed at what I sensed was a certain kind of perhaps inadvertent suppression of Cronenberg’s movies. Robbie told me later that Cronenberg didn’t go to The Last Waltz. ‘Why?’ I said. `Well,’ said Robbie, a little incredulous himself, `they said they couldn’t find him.’

Well, I’m glad he’s finally been ferreted out. I’ve seen The Brood, Scanners and Videodrome in the intervening years. I’m too cowed to look at The Parasite Murders a second time, never mind The Brood; they’re just too disturbing. Cronenberg’s best movies still have the capacity to cause a sort of Jungian culture shock. They’re like Buñuel, or Francis Bacon: wit and trauma, savagery and pity. Within what for most people is a very restrictive genre, Cronenberg has come up with a vision that is genuinely original. Internal metaphors, external horror.

I’ve also had the chance to strike up a friendship with David whom I would never have cast to play himself. I expected somebody who looked like a combination of Arthur Bremmer and Dwight Frye as Renfield in Dracula, slobbering for juicy flies. The man who showed up at my apartment in New York looked like a gynaecologist from Beverley Hills. We had a pleasant dinner, even though there was a certain tension, on my part, probably originating in my expectation that David’s veins would run open and his head would explode. Later, as a birthday gift, David sent me a copy of the uncut Brood. He said it was his version of Kramer vs. Kramer.

I think a lot about his movies. I wish I didn’t. I look forward to the new ones. I wish I didn’t. They still have the old power.

– – – – – – – – – –

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

Originalmente publicado en “Dossier 21: David Cronenberg”

© British Film Institute

1984