¿A todo mundo le gustan los comics, no es así?

Probablemente sí, pero, ¿hace 20 años? Lo dudo bastante.

Enterrado bajo estigmas, vergüenzas y un modelo de distribución y venta fallido, hermético y asfixiante, la industria del comic en Norteamérica enfrentaba su peor debacle en décadas, un auténtico oscurantismo en el cual la ausencia de novedad, un slump en calidad demasiado notable, editoriales en bancarrota, especulación rampante, ausencia de nuevas voces y nulo reconocimiento del mainstream hacían difícil su sustentabilidad a largo plazo.

Pero si algo tienen los comics, es que suelen darle la vuelta al “fin de los tiempos”. Es su mayor virtud, y esta corriente de las artes demuestra en los momentos más duros la capacidad de levantar en un santiamén un terreno fértil para nuevos ciclos de revolución cultural.

En el final de la década de los noventas y en los albores del siglo XXI surgieron textos básicos que le dieron un sustento a nuevas corrientes de pensamiento, que poco a poco fueron cambiando el panorama para la narrativa gráfica, ganando adeptos y pasando de la teoría a la práctica de forma acelerada, imponiendo nuevas tendencias que le dieron lustre y spotlight al Noveno Arte.

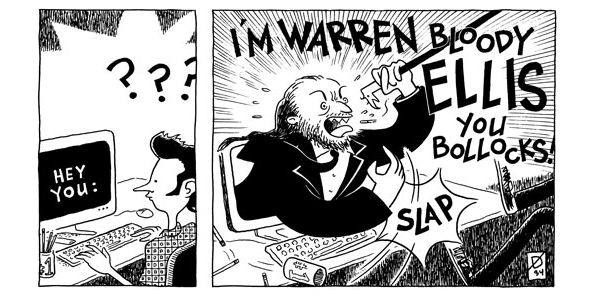

El primero de todos ellos se dio hace 21 años en un simposio organizado en la Universidad de Trieste, en Italia. El conferencista era nada menos que Warren Ellis, que en ese momento había tomado la determinación de sacar a los comics del ghetto y convertirlos en un medio de entretenimiento para todo tipo de público, con temáticas más adultas que las que ofrecían las editoriales más comerciales en ese momento.

“The Last Art; comics, multimedia & the future” describe el estado de la industria en 1998, sus yerros y áreas de oportunidad, haciendo un énfasis en el futuro cercano, en donde la ola digital, la cultura online, el webcomic como microtransacción y la explosión de otros formatos como la antología, el manga y el álbum europeo abrían la alternativa de llevar al comic a una audiencia mayor. Es en este interesantísimo discurso en donde se escucha por vez primera el término de “floppy” como un peyorativo del comic regular de 22 páginas, un objeto literario que hace veinte años estaba en etapa terminal, y había que explorar otras avenidas para resucitarlo o llevarlo al siguiente nivel.

Este es un texto imperdible, presciente y esencial para comprender el génesis de un cambio estructural muy importante que llevó a los comics a otras latitudes.

Publicado originalmente en la columna digital “From The Desk Of” en warrenellis.com, el 21 de diciembre de 1998.

– – – – – – – – – –

University Of Trieste

Trieste

Italy

December 16 1998

“The Last Art; comics, multimedia & the future”

Hello.

I see there’s not much to do in Trieste on a Wednesday afternoon.

Thanks for taking the trouble to show up and sit down. My name’s Warren Ellis. I write comics. That doesn’t mean, as was once suggested to me by a little old lady who will die soon, that I write the little words in the little balloons that the artist so thoughtfully provides. It means that I create the whole damn thing and that the artist does as he or she is bloody well told.

A full script for a comic incorporates prose, the stage play, the screenplay, graphic design and slogan writing. The comic is a bastard form, a multimedia art all its own, a twentieth-century hybrid grown from half a dozen other arts. Elsewhere in Europe, comics are called The Ninth Art. Since no-one’s ever quoted me a Tenth Art, this leads me to wonder if comics aren’t also The Last Art.

I’m a British comics writer working for the American comics market. I’ve been writing since around 1990. Back then, of course, comics were the new rock and roll; comics creators were drinking with pop stars and snorting cocaine from off fresh copies of BATMAN. Only in the last couple of years has my work been available outside the English-speaking countries. This means it’s taken an Englishman most of a decade writing for America to become a European writer, which is faintly ridiculous.

In a time where Europe seems owned by Disney, I feel like I’m part of a dwindling tradition; a comics writer who does not create comics for children. I met an Italian Donald Duck artist in Norway a few months ago. A very nice man, excellent company. But he’s killing me. That bastard duck and his pestilential crowd lay over culture like a smothering blanket. Comics continue to scratch and scrabble underneath it, clawing for air, fighting for light to grow up into. I’m writing at a time where comics are finally becoming an credible, adult art.

And just as we’re getting there, some scumbag happens along to tell us that paper is obsolete and everything worth paying attention to will now happen on computer screens.

Hell, with DVD, we’re now being invited to watch movies on our computer screens, as a matter of preference.

“What I want to do—what I intend to do—is find ways of rebirthing comics, the 20th Century art, for the 21st Century.”

I was brought here, at fantastic expense—which, of course, came from the taxes that you people probably do everything into your power to avoid paying—to talk to you about comics, multimedia, and the future.

This implies not only that comics have something to do with multimedia, but also that comics have a future. This latter note warms my blackened little heart, it really does. In Britain, there’s hardly any comics present, let alone comics future. In America, horrific mismanagement and a general hole where the talent should be has led to a market crash and lots of quick hushed discussions about the future, and whether there is one.

It was the future that made American comics collapse today.

It’s a long and boring story. I’m going to tell you some of it.

It’s all down to Marvel Comics, you see. Marvel Comics was owned by a man called Ronald Perelman, who also owned lots of other companies, like the cosmetics firm Revlon. He bought Marvel and then attached the debt incurred by buying Marvel to Marvel. Which is kind of complicated and sneaky. That kind of thinking is what’s made America the moral and financial paragon it is today. So Marvel suddenly had this large overhead they had to work off. And the only way they could do that was to take over the American comics business—in the short term. In the long term, they’d probably have had to murder that bastard duck and take over Europe too.

And they laid their plans. They pumped out vast numbers of comics, flooded the market with crap. They came up with a scheme to concentrate all the power in comics in one pair of hands by messing up the old comics distribution system. They bought another comics company outright, just to get their hands on that company’s computer colouring department. They paid for their own area on America Online, the USA’s most popular Internet service, and attempted to create “cyber-comics”. All in an attempt to seize the future for themselves.

They went bankrupt.

“The American comic is an important mass-culture artifact…”

Today, Marvel is barely even a shadow of itself. There’s even a possibility that it could cease to exist as a publisher of new comics by this time next year. Their plan to concentrate all the power in comics into one pair of hands worked like a dream. Unfortunately, it wasn’t their hands that the power went into. The computer colouring department was well-known as a disastrous mess before Marvel bought it, because they never bothered to learn one of the crucial lessons that our multimedia future has to teach us—computer wizardry and the ability to wave a mouse about is nothing without an aesthetic intelligence. Computers alone do not make art.

And the “cyber-comics”, well.

Here’s where we get to it.

We live in a time where all our narrative arts are being reconfigured and reimagined to be accessible by computer.

I like computers. I have three. Big workstation. Little laptop. Small handheld computer that fits in my inside jacket pocket. I have nothing against them. If I sometimes squint and glare at the idea of making everything on the bloody planet fit on the computer screen, then it’s because I’m thirty years old and too attached to things like paper, and groping my girlfriend in the back row of the cinema, and listening to a live band in a sweaty smoke-filled club, as opposed to reading text onscreen, and shoving a movie into the DVD-ROM drive, and listening to a gig over Real Audio on the computer speakers.

But these things are happening. The future dictates that we will have to fight for things like FLUXUS to keep happening.

Comics on computer may not work. This doesn’t bode well for our future.

“This implies not only that comics have something to do with multimedia, but also that comics have a future…”

American comics are no longer a particularly cheap artform. Time was they cost next to nothing and were thick like a paperback novel. The average modern American comic—a floppy, 32-page thing released monthly—costs about two dollars fifty cents, American. It takes about five, ten minutes to read. You can go and see a movie there for six or eight dollars and hopefully be entertained for ninety minutes or two hours. You can buy a 200-page magazine for five dollars. Comics don’t match up to this kind of content-to-cost ratio. American comics, anyway. The Japanese comics, the manga, are still vastly popular, and both the classic anthology format and the album have yet to die out in Europe, thank God. But the American comic is an important mass-culture artifact. It needs to find away to become that again, not an expensive artform available only to the financially comfortable and the crazed collector.

And that’s why comics on computer have to work. But the Marvel cyber-comics…

…well, here’s what they did right. They weren’t bound by tradition. The comics pages they created fitted the dimensions of the computer screen, by design.

(pause)

That’s it, yeah.

I think the biggest problem I had with them was that they all had bloody Spider-Man in. Oh, and the wonderful little high-tech animations, whereby you could see Spider-man’s arm do this (move arm up and down stiffly).

Oh, and you could only see these cyber-comics if you joined America Online, of course. I think you got something like four pages every week or two, at the project’s height.

I imagine Marvel received some kind of micro-payment every time their comics were accessed. I hope they did. Because that opens up possibilities. But the rest of it, to my old eyes, looked disastrous.

“Comics is the most accessible of visual media. Comics are nothing but words and pictures.”

Understand, I’m not looking to multimedia etc. to replace paper, to replace the standard modern comic. (Although we do need to look at formats again, but that’s another lecture, best given to an audience that’s already drunk.)

What I want to do—what I intend to do—is find ways of rebirthing comics, the 20th Century art, for the 21st Century.

Comics is the most accessible of visual media. Comics are nothing but words and pictures. And you can do anything with words and pictures, and do it quicker. And all you need is a pair of working eyes. You don’t need a film projector, or a television set. You need a handful of change, a vocabulary, and the power of sight. They’re an educational tool, a documentary medium, the fastest visual fiction on Earth. Marginalised though they are in Western culture, comics are the most powerful of arts. Bastard form though it may be.

Having said that. It seems that we’re rushing towards a time where computers will be with us as ubiquitously as our pocketful of change. Hell, I’ve recently seen a wearable computer that fits in the pocket, with a viewscreen that hangs over the eye. Hell, I could afford it. It costs about half as much again as the PC I bought four years ago. I already have a computer in my jacket. Of course, it’s the jacket I left at home, but you get the point.

Comics needs to configure itself to these onrushing times. Not as the be-all and end-all of the medium, but as a station in the future. And it’s feasible, it’s doable. Next year, I’m going to begin writing downloadable serialised comics. They’ll be available for free, at first. If I can find a way to make them pay through micropayments, so that the artists don’t complain of starvation too often, then I’ll do that too. But the economics of the thing are not why I’m doing it.

I’m doing it because not enough other people are. I’m doing it because, through the Internet, comics have been injected into world culture. I was hired to attend this event through the Internet. Comics have been injected into world culture, via the Internet—and the Internet puts everyone on a level footing. The same rung of the ladder. I can have a website and so can Microsoft and it’s no more difficult to access one or the other. Which means, haha, that I’m on a level footing with that bastard duck. On the Net, it’s me versus him, neither of us having vast advantage over the other. Or at least if either of us have advantages, each is cancelled out by the other’s. He’s got more money, but I can react quicker.

“Through the Internet, comics have been injected into world culture.”

Through the Internet and other multimedia manifestations, comics, the original bastard mixed-media form, can stand level with the other artforms that make up our culture, and say “I’m as old as any of you, and of as much worth as any of you, and here’s why”—and SHOW you. We can gather our maturity and our intelligence and the mad need to tell adult stories that keeps us in comics in the first bloody place and SHOW you—CHEAPLY. The future of comics is its return to being an artform for the masses, as broad and deep and bright as film or television. Brighter, even.

They brought me here to talk about comics, multimedia, and the future. Comics; the power of film, the speed of television, the depth of prose, the beauty of illustration, the accessibility of the computer screen. I’m here to tell you that comics ARE the future.

Thank you.

– – – – –

With thanks to Lorenzo, to Matteo, to Daniela and Fabiana and Ricky (?) and the rest of the fine people of La Cappella Underground, and, of course, to Elisa, my interpreter. More on my visit to Trieste as part of La Cappella Underground’s FLUXUS event later.

– – – – –

Warren Ellis

Trieste, Italia

Southend, England

21 December 1998

“Marginalised though they are in Western culture, comics are the most powerful of arts.”